weekend blog

Back to slightly more serious stuff. But nothing too controversial. Here’s an aspect of our greedy, self-serving, net-zero-obsessed, incompetent government of which readers might not have been aware:

Yes Ministers?

One of the many ways for MPs to increase the amounts of our money they can pocket is by becoming government ministers. In the Westminster Parliament we have around 95 MPs who are also paid ministers. This means that more than one in four of the 360 Conservative MPs are also government ministers of some sort. In addition there are around 14 salaried government ministers from the House of Lords bringing the total of Westminster government ministers to 109.

This high number of government ministers at Westminster was something that even our parliamentarians were beginning to question. In 2010 the Public Administration Select Committee examined this issue. In its inquiry Too Many Ministers? the Committee found that the UK Government was an international outlier when it came to ministerial numbers; employing more ministers than India, Canada and South Africa.

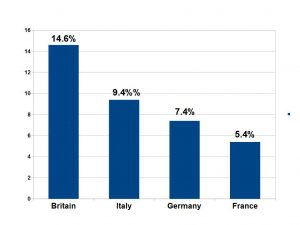

In 2011, the House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee wrote a report entitled Smaller Government: What Do Ministers Do? In this report, the Committee noted that Britain had many more paid ministers than most other European countries. With just under 15 per cent of British MPs, being paid ministerial salaries, British citizens benefit from considerably more government ministers than countries like Germany, Italy and France which also have around 600 members of their lower houses but where they had, in some cases (Germany and France), around half or even fewer than half the percentage of MPs being ministers compared to Britain:

Percentage of MPs being paid ministerial salaries in the larger European countries

The House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee was concerned about the effects on our democracy from having so many ministers:

Having too many ministers is bad not just for the quality of government, but also for the independence of the legislature. The Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975 limits the total number of ministers at 109 but this is regularly exceeded by appointing unpaid ministers. In addition, the existence of Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPSs) who, while not ministers, are expected to support the Government in all divisions in the House, further increases the size of the payroll vote. Currently 141 Members� approximately 22% of the House of Commons�hold some position in the Government. This is deeply corrosive to the House of Commons primary role of acting as a check on the Executive as all government ministers are expected to vote with the Government.

As one former political adviser explained to the Commons Public Administration Committee, �if the Prime Minister has his way, he would appoint every single backbencher in his party to a ministerial job to ensure their vote�.

Appointing MPs to ministerial positions is also a good way for prime ministers to reward loyalty. So perhaps we�re very lucky that the Ministerial and Other Salaries Act (1975) limits the number of paid ministers to 109, though governments often exceed this number by appointing unpaid ministers in addition to the lucky 109 who are fully paid.

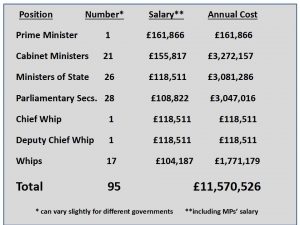

The Commons Public Administration Committee found three main problems with there being so many ministers in Westminster. Firstly, they were hugely expensive �placing a burden on the public purse�. The amounts we pay our 95 MPs who are also government ministers could seem quite generous to ordinary British taxpayers whose average salary is in the region of �24,600:

Cost of MPs who are also paid government ministers

Secondly, the Committee felt that having so many ministers reduced the ability of the House of Commons to hold the Government to account. As all ministers were expected to support the Government in the Commons, by making so many MPs into ministers, the Government ensured their support by creating what was called a �payroll vote� � anyone either getting or hoping to get the benefits of a nice ministerial salary and other perks of office would be unlikely to jeopardise this by ever voting against the Government. As the Committee warned, �the temptation to create more and more �jobs for the boys� (and girls) is not conducive either to better government or better scrutiny of legislation�.

And thirdly, the Committee was concerned about the poor managerial qualities of many ministers. As one contributor to the Committee explained, �very few ministers have ever run anything. There is no way you are going to convert them into good managers�.

Former ministers and civil servants appearing before the Committee also expressed concerns about having such a large number of ministers when there really wasn�t enough work for them all. A former minister remarked, �I think there has probably been an increase in pointless activity�. And a senior civil servant seemed to be suggesting that the large number of ministers was more linked to the Prime Minister�s desire to hand out well-paid favours and ensure support rather than the number being driven by the real quantity of work to be done. The civil servant explained how officials spent far too much time trying to find things for the hordes of junior ministers to do:

The more junior ministers you have � and we have more junior ministers than ever � the more work you have to find for them. One of the biggest single frustrations of the political process within the civil service is just the number of junior ministers you have and the work projects that have to be designed and engineered at a political level.

The Committee also concluded that: ‘The ever-upward trend in the size of government over the last hundred years or more is striking and hard to justify objectively in the context of the end of Empire, privatisation, and, most recently, devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland’. Given that there are another 28 ministers in the Scottish Parliament, 14 in the Welsh Assembly and 10 in the Northern Ireland executive, people from outside of politics might have imagined that this flourishing in ministerial numbers in the regional assemblies might have reduced the need for so many ministers in Westminster.’

The Government’s response to the Committee’s recommendation to cut the number of ministers was the usual bureaucratic ‘get lost’ that we should have become used to when any part of the public sector is faced with even the mildest suggestion as to how it might improve its performance and/or reduce its costs to the taxpayer.

The Government thanked the Committee for its work:

The Government welcomes the Committee’s interest in the role and appointment of Ministers, continuing that of their predecessor Committee whose report ‘Too Many Ministers’ (Ninth Report of Session 2009-10 HC 457) gave this Government considerable food for thought when making appointments in May 2010. The Government currently has 121 Ministers, including 95 in the Commons, and is keen that they perform their roles effectively and flexibly, rising to the challenges of the day particularly in the light of the necessary impetus to reduce the deficit.

But the Government rejected any suggestion that the number of government ministers could be reduced towards the level of comparable legislatures in other countries in order to save British taxpayers money:

The Government is grateful for the Committee’s views on these issues. As the Committee knows, the Government has been clear that it wants to strengthen Parliament, and to look at the issue of the size of Government and the balance between the two Houses in the round. It would not for example be appropriate to only consider the limits in the Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975. To this end, the Government will keep the number of Ministers under review particularly in the light of its proposals on House of Lords reform and changes to the number of Parliamentary constituencies.

However, the Government believes that a reduction to 80 ministers shared between the Commons and the Lords over the course of this Parliament as suggested by the Committee is unlikely to be a realistic aspiration.

Since then, all ideas of reducing the number of government ministers have been quietly shelved and the ministerial gravy train can keep trundling happily along, possibly more for the benefit of Westminster’s many ministers than for Britain’s increasingly impoverished taxpayers.

�I think there has probably been an increase in pointless activity�.

Exactly. This is apparent as the parasitic state slowly kills the host. Even more depressing is this is now happening across all western countries.

Following on from my comments yesterday, at least in England those 109 ministers have been voted for by the public.

In Scotland there are all sorts of quango organisations set up to look at various aspects of interest to the public but the people who chair these set ups are not voted for and are the result of appointments made at the whim of the First Minister.

This is dangerous for very obvious reasons.

The problem is that the Scottish public are unaware of these arrangments and probably don’t care as Britain’s Got Talent will be on in five minutes.

This is what you get with political parties. The MPs all want to be recognised for the extra money. The ones appointed to posts will not criticise the government and the rest are waiting for an opportunity to get their snouts in the trough. The same applies to the opposition, they all want to be in the next government. We don’t matter to any of them. The purpose of parliament is to hold the government to account. It has failed to do this for years.

As far as costs are concerned it is necessary to add in the army of civil servants, mostly enjoying working from home. And don’t forget the secure pensions at the end of it all.

I see that the non conservatives are again promising to cut all the wasteful administration,election coming up just a co incidence? How many times is this? They obviously know it exists and is a drain on our productive economy,that which still exists.So why,why have they continually promised but followed up with total inaction?

Answer,they know they can rely on the sheep to keep be?ieving their lies.Or perhaps they really have a far different agenda?